Public Libraries’ Novel Response to a Novel Virus

America’s public libraries have led the ranks of “second responders,” stepping up for their communities in times of natural or manmade disasters, like hurricanes, floods, shootings, fires, and big downturns in individual lives.

Throughout all these events, libraries have stayed open, filling in for the kids when their schools closed; offering therapeutic sessions in art or conversation or writing after losses of life; bringing in nurses or social workers when services were unavailable to people; and hiring life-counselors for the homeless, whom they offer shelter and safety during the day.

Today, interventions like those have a ring of simpler days. But libraries have learned from their experience and attention to these previous, pre-pandemic efforts. They are pivoting quickly to new ways of offering services to the public—the core of their mission. When libraries closed their doors abruptly, they immediately opened their digital communications, collaborations, and creative activity to reach their public in ways as novel as the virus that forced them into it.

You can be sure that this is just the beginning. Today libraries are already acting and improvising. Later, they’ll be figuring out what the experience means to their future operations and their role in American communities.

Here are some of the things libraries are doing now. These are a few examples of many:

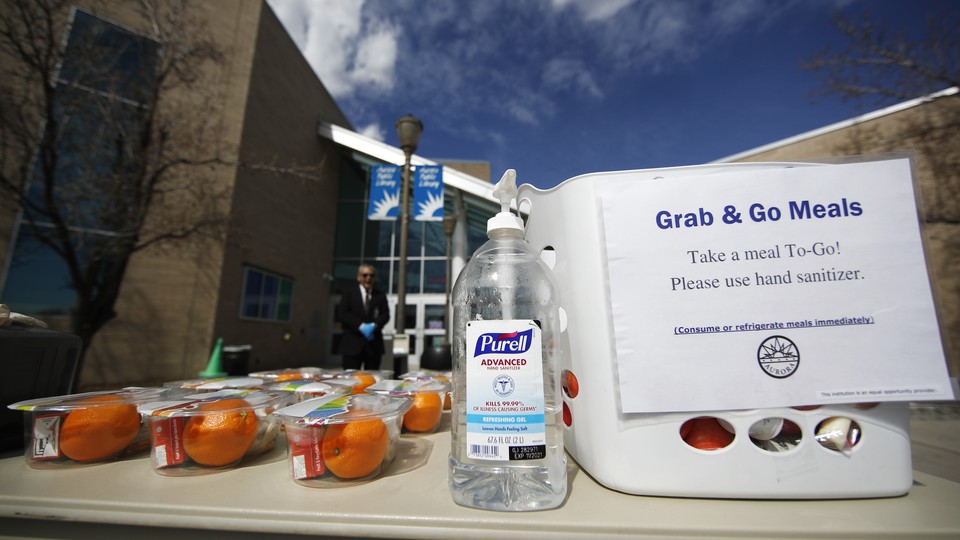

Feeding the hungry: While schools have traditionally supplied lunches and breakfasts for American schoolchildren who economically qualify for them, libraries have always stepped in for after-school snacks and summertime food programs.

With schools now closed, more libraries have become drive-through or pick-up locations for grab-and-go meals. This is happening in St. Louis County, for example, which is collaborating with Operation Food Search, a nonprofit that distributes free drive-through food pickups in nine of their libraries.

In Columbus, Ohio, the Columbus Metropolitan Library closed so quickly that they were left with nearly 3,000 prepared meals on hand. They collaborated with the Children’s Hunger Alliance, which had supplied the meals, to recover, repurpose, and distribute the packets at three library locations.

In Ohio, the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County, together with the United Methodist Church food ministry are offering ready-to-eat meals to all children 18 years old and under.

3-D printing of PPEs and PPE collections: Many libraries are putting the 3-D printers from their makerspaces into use.

In Maryland, the Prince George’s County Memorial Library System has sent two of its 3-D printers home with a staff person to soon begin printing shields for health workers’ masks. The library is donating labor and materials for this effort, and like other organizations around the state, is working with Open Works, Baltimore’s biggest makerspace community, to make sure everyone is compliant with specs for the production of the shields.

Internationally, the Milton Public Library in Ontario, Canada, has partnered with Inksmith, an education technology company, to print face shield headbands for PPE masks.

The Billings, Montana, public library is 3-D printing face masks for health care workers.

The McMillan Memorial Library in Wisconsin Rapids, Wisconsin, is 3-D printing masks for the community. The Cedarburg Public Library in Wisconsin is 3-D printing masks for the fire department.

The Oakland, California, library has repurposed bookdrops to collect new, packaged masks.

Providing round-the-clock Wi-Fi access and hotspots: Aware that many of their customers rely on the library as their only point of Wi-Fi access, libraries in many communities leave their Wi-Fi open after closing hours. Those numbers are increasing. Also, many libraries have loaned out the entire supply of their portable hotspots to school children who need internet connection to do at-home school work. Others have purchased more hotspots to begin filling the gaps.

The Brightwood Branch of the Indianapolis Public Library made sure all the hotspots they possessed through a Grow with Google partnership were checked out before their closed their doors.

Taking care of the homeless: In Washington State, the downtown Spokane Public Library has opened as a temporary homeless shelter.

In San Luis Obispo, California, the parking lot of the Los Osos Library remains open as a designated safe and clean space for homeless people who live in their cars to camp overnight.

The Richland County Library system in South Carolina, working with the United Way, collected and delivered their 40 standing hand-sanitizing stations to local homeless shelters. They also bought and placed porta-potties outside their downtown libraries.

Keeping people productive, safe, healthy, informed, and connected to each other: Many libraries have ramped up their online presence. There are lists and lists of resources for children’s activities; plans for improving adult job skills and dealing with job loss; hobby ideas; reading lists; ways to sleep better, meditate, and stay calm; ways to exercise; and ideas for virtual, social interaction.

Also, libraries have always been trusted sources of information. Many are revising their websites and scaling up their social media for multiple purposes: bringing in more users and broadcasting the message of their diverse, digitally-available holdings; posting timely, accurate, curated information; and offering up-to-date public-service information on local efforts and issues like city services, public advisories, health directives and requests, tax and unemployment issues, and of course, COVID-19 resources.

From the Anythink libraries in Colorado, Erica Grossman wrote to me in an email: “We’re working swiftly to become a virtual town square—a place of information and connection.”

Here is a grab-bag of examples of the trend she is discussing:

- In San Francisco, libraries and rec centers are becoming emergency childcare centers for workers on the front lines of emergency work.

- In Ohio, the Toledo Lucas County Public Library system has offered its vehicles to those delivering food supplies.

- The Birmingham Public Library in Alabama has a list of valuable links, including one that shows exactly where to get tested and includes details of hours, location, and necessity for call-ahead appointments.

- The Columbus, Ohio, library informs the community about blood drives by one of their partners, the American Red Cross.

- Before they closed, the Prince George’s County Memorial Library System had placed a dedicated computer in each branch to help people complete their 2020 census forms online. Now, the library’s Nick Brown described to me how they have pivoted to virtual programming to keep the interest strong and the completion rates high—this in a county that was determined to be undercounted by 30 percent in the 2010 census.

- In Anchorage, Alaska, the city’s emergency operations system has moved into the Loussac Library building, with its ample space and robust Wi-Fi connectivity.

These are the early days of both COVID-19 and the creative ways that libraries will respond to it.